This post examines how the academic publishing business model relies on unpaid academic labor, public funding, and prestige-based incentives, and how common productivity metrics in academia quietly reinforce that system.

Researchers write the articles.

Academics review the articles.

Academics edit the journals.

Universities pay the salaries.

Libraries pay the subscriptions.

Yet academic publishers continue to generate billions in profit.

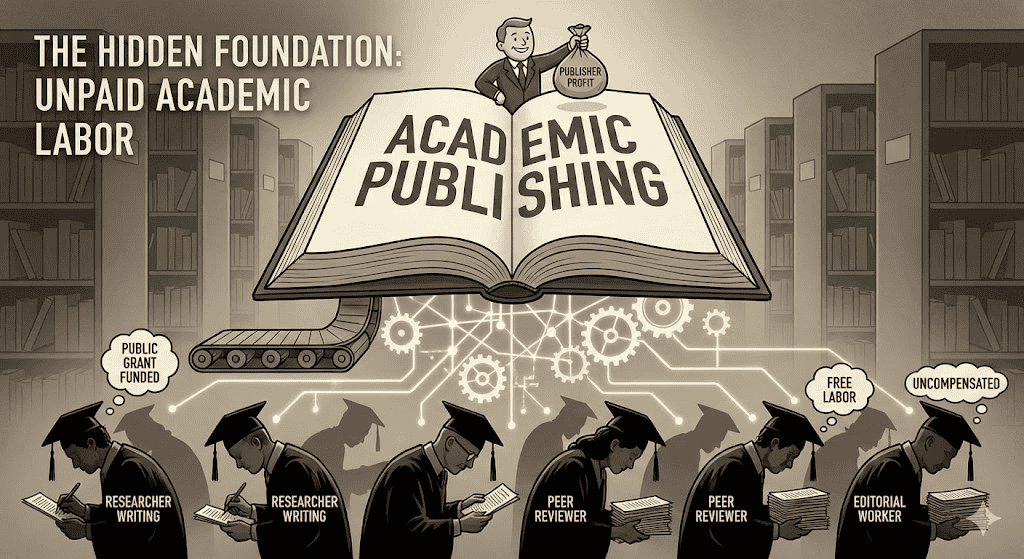

The Unpaid Labor Behind Academic Publishing

Most people outside academia are surprised to learn how much unpaid labor supports academic publishing.

Researchers write articles on their own time, often funded by public research grants. Other academics perform peer review for free, in the middle of their busy schedules. Editorial work is frequently uncompensated or only symbolically recognized.

This unpaid academic labor is not peripheral. It is central. Without it, scholarly journals cannot function.

Yet once published, the people who created and validated the work typically retain no ownership and receive no share of the profits it generates.

Copyright Transfer: Normalized, Not Neutral

In many academic journals, publishing a paper requires signing something called a copyright transfer agreement. While the specifics may vary, the outcome is usually the same: authors give up ownership of their work in exchange for publication.

This is often treated as a formality. It shouldn’t be.

To someone outside academia, the arrangement looks strange. An author creates original work, often funded by public money, and then hands over exclusive rights to a private company—without payment—as a condition of having the work recognized.

The issue is not legality. It’s proportionality.

It is unusual and worth questioning.

At a minimum, it’s fair to ask why authors typically retain so little (virtually none) control over work they produced, reviewed, and revised themselves (other than a lousy ‘kudos’ to raise their egos).

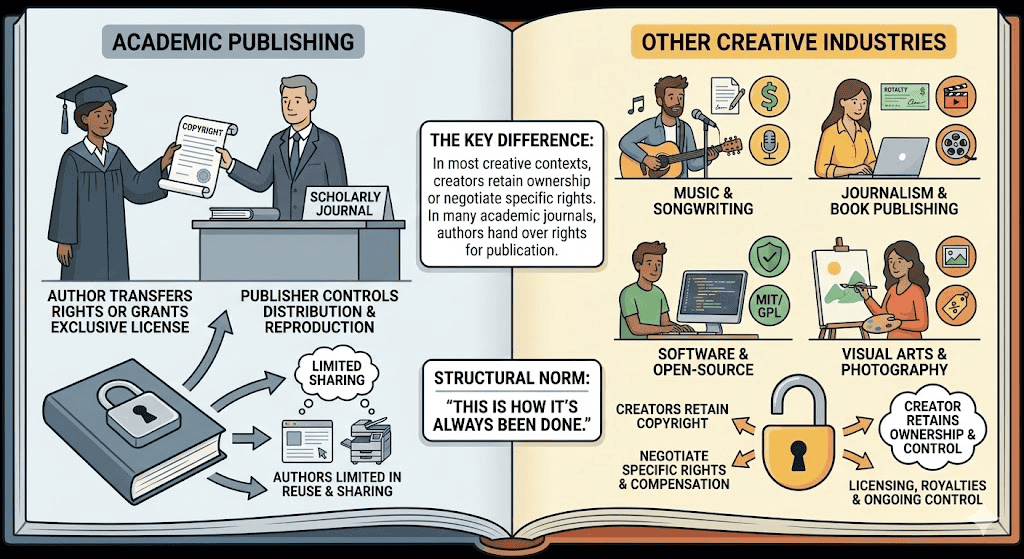

How Academic Publishing Differs from Other Creative Industries

In academic publishing, the norms around rights and ownership are quite different from most other creative fields.

In traditional scholarly journals, authors often transfer copyright or grant an exclusive license to the publisher as a condition of publication. Once this transfer occurs, the publisher becomes the copyright holder and controls key rights such as distribution and reproduction. It may limit the authors in how they can share their own work—for example, by posting it on personal or institutional websites, distributing copies, or reusing material—unless the contract explicitly allows it.

Even when some rights are retained, they are typically limited and defined by the publishing agreement rather than the author’s default ownership.

In contrast, in many other creative industries:

- Journalism and mainstream book publishing: Authors and journalists normally retain copyright and either license rights to publishers or negotiate royalties. Authors are often paid advances and continue to earn income, and rights like film or merchandise can be separately negotiated.

- Music and songwriting: Composers and performers typically control their copyrights and negotiate with record labels; royalties and licensing are standard.

- Software and open-source work: Creators choose licenses that explicitly govern how their work can be used (e.g., MIT, GPL), giving them ongoing control over distribution and modification.

- Visual arts and photography: Artists retain copyright and typically license specific uses (e.g., reproduction, merchandising) rather than surrender ownership.

The key difference is that in most creative contexts, creators retain ownership or negotiate specific rights and compensation. By contrast, many academic journals require authors to hand over the rights that allow publishers to control and monetize reuse and distribution in exchange for publication and prestige.

That’s not a moral failing on the part of individual publishers or researchers. It’s a structural norm that has gone largely unquestioned because “this is how it’s always been done.”

Further reading:

Where the Money Comes From and Why the Public Should Care

When academic publishing does involve money changing hands, it’s rarely personal.

Libraries pay subscription fees. Researchers pay open-access fees typically through research grants or university funds. Those funds are often rooted in taxpayer dollars.

So the public pays for:

- Research to be conducted

- Researchers’ salaries

- Publication of the results

- (and sometimes) Access to the same results

This doesn’t mean publishers are doing something illicit. But it does mean the flow of money is worth examining, especially when profits are high and ownership is concentrated.

This is not just an academic concern. It’s a question of how publicly funded knowledge is managed and monetized.

What Publication Metrics Actually Measure

Things like publication counts, journal prestige, and citation metrics are the currency that shapes academic careers. These numbers are often proxies for quality, insight, or impact.

In practice, they measure something else quite well: participation in the publishing economy.

Every paper submitted and accepted:

- Adds content to publisher catalogs

- Triggers an unpaid peer review

- Strengthens journal brands

- Expands monetizable archives

When institutions reward quantity without interrogating ownership or value distribution, they are not just measuring scholarship. They are reinforcing a particular economic arrangement.

This doesn’t mean publishing is bad. It means publication counts are a narrow and easily misinterpreted metric.

Why the System Persists

Academic publishing persists in its current form because it aligns incentives:

- Publishers gain content and prestige

- Institutions gain evaluation tools

- Researchers gain career signals

Each participant acts rationally within the system, even if the system itself produces lopsided outcomes.

That’s why critiques focused only on individual behavior miss the point. The issue isn’t bad actors. It’s a structure that quietly separates labor from ownership and then treats participation as merit.

The Question Worth Asking

The real question isn’t whether publishers add value. To be fair, they do.

The question is whether a system built largely on unpaid, publicly funded labor should grant exclusive ownership and disproportionate profit to intermediaries, and then use participation in that system as a primary measure of academic success.

Until this question is confronted directly, reforms at the margins won’t matter.

The system isn’t broken.

It’s working exactly as designed.

Just not for the people doing the work.

Conclusion

If knowledge is a public good, then how it is owned, measured, and monetized should be open to public discussion.

Prestige may sustain the system.

But transparency is what will ultimately change it.

P.S.: Shhh… don’t tell anyone I’m writing this out of mild annoyance. It’s that time of year when academics are almost forced to stop doing research and start documenting that they once did research for an annual performance review.

Also, to publishers who keep spamming my inbox: stop asking me to serve on your editorial board unless you’re finally ready to compensate labor instead of complimenting it.

Leave a Reply